Current public health threats, their global governance and the national policies addressing them: the case of the pandemic of Coronavirus (Covid-19), Policy Brief #1

Current public health threats, their global governance and the national policies addressing them: the case of the pandemic of Coronavirus (Covid-19)

Policy brief 2020.1

Current public health threats, their global governance and the national policies addressing them: the case of the pandemic of Coronavirus (Covid-19)

© CEHP | Center of Research & Education in Public Health. Health Policy & Primary Health Care

Thessaloniki, 12 March 2020

Authors:

Elias Kondilis

Associate Professor of Primary Health Care - Health Policy

Alexis Benos

Professor of Hygiene, Social Medicine & Primary Health Care

Aknowledgements to Arianna Rotulo (PhDc), John Pantoularis (MD) and Stergios Seretis (PhD), members of the Global Health & Political Economy of Health Research Team and Magda Gavana (PhD), Research fellows of the AUTH Laboratory of Primary Health Care, General Practice and Health Services Research for their critical points and positive proposals.

Introduction

The ongoing coronavirus epidemic (covid-19) has generated genuine worry and an unprecendent mobilisation in global and national level.

Up to 12 March 2020 125,048 cases were recorded in more than 110 countries and a bill of 4,613 deaths.1 65% of the cases and 68% of the deaths were recorded in China. The unquestioned colossal reply of the chinese authorities,2 presented by WHO as «the more ambitious and aggressive disease control programme in the history of public health”,3 seems to have accomplish - at least temporarily - the control of the spread of the disease in this country. Nowadays leading position in the spread of the disease has been taken by Italy, South Corea and Iran with more than 8-12,000 cases per country.1

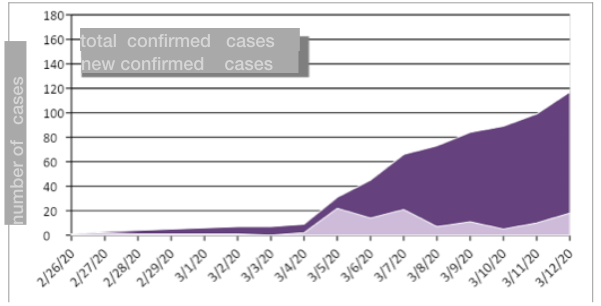

In Greece the first diagnosed coronavirus case was recorded on the 26 of February 2020 and within two weeks the number of cases raised to 117 (Figure 1). 29.1% of the cases are hospitalised, 3,4% in ICUs whereas 65% of the cases are under home restriction.4 ΕΟDΥ[the greek CDC] is not announcing in a daily basis the number of diagnostic tests. Meanwhile through the press releases it is estimated that the first week of the epidemic, 570 tests were performed and 1610 during the last ten days [1610 tests in all]. 4,5

Figure 1: Coronavirus cases (covid-19), Greece  Note: up to the 12th of March EODY was not publishing any report of epidemiologic surveillance of the coronavirus epidemic

Note: up to the 12th of March EODY was not publishing any report of epidemiologic surveillance of the coronavirus epidemic

Source: authors’ estimations based on the EODYs’ press releases.

The global governance of the coronavirus epidemic

The coroanavirus pandemic started the 31st December 2019 with reports of pneumonia cases of unknown ethology [related with an open animals’ market in Wuhan. It was identified when the chinese authorities specified, the 7th of January 2020, as cause of these pneumonia cases a new strand of coronaviruses (2019 n-CoV). WHO characterised the epidemic as urgent global threat the 30th of January 2020 and finally as a pandemic the 11th of March of the same year.6,7

The evolution of a local epidemic to a global threat is not an unknown experience for the international community. In the recent years we had the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic in 2003, which generated global panic with 8,096 cases and 774 deaths, the influenza H1N1 epidemic in 2009 in Europe and Asia, the MERS-CoV (Middle-East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus) epidemic in Middle East countries in 2013 και recently the Ebola epidemic in 2014-15 in West Africa countries.8

What is at stake in such events of threats in global level, obviously related to the biological characteristics of the viruses causing these epidemics, is the preparedness, the funding support and the effectiveness of the international community to reply to these threats.

The response, for example, to the 2003 SARS epidemic (despite the easy transmission of the virus and its relatively high fatality rate) was ultimately judged to be relevant and timely,8 and the experience of the SARS threat has driven WHO to the revision and extension of the International Health Regulations - 20059, which is the updated regulatory framework currently used for the identification, epidemiological surveillance and control of the current coronavirus epidemic (covid-19).

Τhe international response to the Ebola virus epidemic has not been as successful though. From December 2013 to April 2015, amid a global economic crisis and the generalisation of restrictive policies internationally, the Ebola epidemic has hit Western African countries (Liberia, New Guinea, Sierra Leone) leaving behind 26,000 cases, 11,300 deaths, 500 of which were health professionals (almost 2-8% of the healthcare human capacity) and over $ 53bn. economic damage.10,11,12

The intervention of international transnational organisations in the Ebola epidemic has been described as delayed (the epidemic was recognised as a global threat 20 months after its outbreak), financially inadequate and operationally ineffective.11,13,14 The output of this international failure in controlling the Ebola epidemic, was the revision and introduction of new financial instruments at international level to deal with emergencies (Table 1), which were designed within the framework of strict budgetary discipline during the Great Recession 2008-15) and are now activated by international intergovernmental organisations to address and control the current coronavirus pandemic.

|

Table 1. Transnational funding mechanisms to tackle the coronavirus epidemic (Covid-19) – March 2020 |

||

|

Funding body |

Funding tool |

Explanation |

|

World Health Organisation |

Contingency Fund for Emergencies - CFE |

The aid fund was set up in 2015. For the treatment of coronavirus, WHO mobilised $ 9 million from the fund's reserve |

|

2019-nCoV Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan |

It is an emergency aid mechanism to deal with the coronavirus epidemic for the period Feb-April 2020. WHO appealed for $ 61 million |

|

|

World Bank |

Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility – PEFF |

An aid mechanism set up in 2016. It is a "pandemic, catastrophic bond" worth $ 320 million over three years. |

|

Immediate support for Covid-19 country response |

On March 3th, the World Bank announced the possibility of providing loans totaling $ 12 billion to medium- and low-income countries to deal with the effects of the coronavirus epidemic. |

|

|

International Monetary Fund |

Rapid-disbursing Emergency Financing Facilities |

On March 3th, the IMF announced the possibility of providing loans totaling $ 50 billion in low-income countries and emerging economies to deal with the effects of the coronavirus epidemic. |

|

Note: the first three financial mechanisms of the table are mechanisms of international assistance, the last two are mechanisms of loan provision | Source: author's elaboration based on data from 15,16,17,18 |

||

Although it is early enough to fully evaluate the global governance of the current pandemic, a number of observations raise concerns.

WHO recognised the danger of the spread of the new coronavirus epidemic and activated the global alert mechanism relatively early. It even devised a strategic plan to tackle this new threat, with the main aim of limiting its spread and minimising its social and economic impact.19 However, for the implementation of this strategic plan only $ 9m. were raised from the Emergency Fund (CFE), which is financed by regular contributions from Member States and was forced to call for an additional $ 61m. by donations and extraordinary state contributions.15 By 12 March 2020, WHO had raised the disappointing sum of $ 51m. of which 40% came from Chinese contributions, 20% from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation donations, and 30% cumulatively from US and UK contributions.15

The second funding pillar to support the strategic plan to tackle the coronavirus pandemic are the revenues from the "pandemic, devastating bond" issued by the World Bank on behalf of its 77 developing Member States (Supplementary Text 1). The purpose of the bond as cited by the Bank's statement, is to safeguard adequate financing from third parties (i.e. financial markets) in a timely manner during the early stages of the crisis, crucial for controlling pandemics when they are still at the beginning of their development.20

|

Supplementary text 1. The World Bank pandemic catastrophic bonds |

|

|

The role of the World Bank |

Pandemic bonds (PEFF) with a total value of $ 320 million were issued by the World Bank on behalf of 77 developing Member States and have a three-year term (expiring in July 2020). Demand for bonds was twice as high as supply, and a second batch of bonds is expected in May 2020 (PEFF2). The pandemic bonds cover, among other things, the risk of coronavirus epidemics (eg. SARS, MERS), including obviously the current new strain (2019 n-CoV). |

|

The role of markets |

Bondholders (speculative, private funds) receive an annual interest rate of 13% and in case of non-epidemic at the expiry of the bond, they receive back all their capital. In case of an epidemic, they lose part of their initial capital. |

|

Compensation criteria for affected countries |

In case of an epidemic, Member States, in whose name the bond was issued, receive compensation if, of course, a number of criteria are met: (1) the compensation is received 12 weeks after the onset of the epidemic (2) At the time of the epidemic, the epidemic must be active (3) at least 250 deaths must have occurred during the epidemic (4) the epidemic must have caused at least 20 deaths in at least two countries. |

Source: author's elaboration based on data from 12,16,20,21

A series of empirical studies has, a long time ago, annulated any expectations of this emergency funding mechanism. The Bank's pandemic bonds may be resold on the secondary market creating speculation conditions,16 generating incentives for governments to delay responding to epidemics in order to meet the criteria (high number of deaths) for receiving compensation,16 which is, for the affected countries, often uncertain, small and delayed.12,21 They are not a social protection institution, but another area of potential investment profitability. Indicatively, from 2017 to 2019, the World Bank had paid bondholders over $ 114m. in interest, whereas the affected countries in the same period had received only $ 51m in aid.20

The national policies responding to the coronavirus epidemic

Irrespective of and beyond the necessary transnational cooperation and assistance in conditions of global public health threats, the ultimate responsibility for protecting the health of the populations lies with the national states and their health systems.19

In the case of the coronavirus pandemic, health systems at international level, and in particular in Europe, are called upon to tackle the pandemic challenge, still bearing the brunt of perennial austerity and privatisation policies during the crisis, with low levels of public spending for health, tired and lacking health care staff and inadequate to the needs public health structures.22,23

The vulnerabilities or not of any health system will largely determine their ability to control the epidemic at national level and to manage as far as possible its impact on the health of populations.

A typical example of the above is the case of Italy. Since 2002, its national health system has implemented a fiscal decentralisation program, under which each region is responsible for both the organisation of health services (and in particular public health services) and the allocation and use of part of the necessary funding resources at regional and / or local level.24 The result of this neoclassical reform is a multi-speed health system, fragmented in its operation. This crucial vulnerability of the Italian health system has played a decisive role in spreading the epidemic in its early stages. According to data available so far, the lack of communication and exchange of information between Lazio (Rome) and Milan (Milan) regional public health services has delayed the official recognition of the outbreak in the country by three weeks,25 giving it enough time to spread significantly (Table 2). WHO’s experts who visited Italy on 6 March noted the urgent need to develop a national epidemiological surveillance strategy in order to achieve effective control of the epidemic in Italy.26

|

Table 2. Coronavirus (Covid-19) epidemic: the situation in Italy and Greece |

||

|

Italy (21 Febr to 12 March) |

Greece (26 Febr to 12 March) |

|

|

All Confirmed cases |

15113 |

117 |

|

Actual positive cases (12 March 2020) |

12839 |

114* |

|

All deaths |

1016 |

1 |

|

All recovered cases |

1258 |

2 |

|

Home restriction |

5036 |

76 |

|

Inpatients in hospitals |

6650 |

34 |

|

Inpatients in ICUs |

1153 |

3 |

|

Note: (*) own calculations without counting the possibly home restricted recovered cases |Source: authors’ analysis based on 4,27 |

||

Correspondingly, the main vulnerabilities of the Greek health system are the lack and aging health care staff of the National Health Service, the inadequate health and safety conditions of public hospital workers (situation which could, potentially and following the epidemic trend, lead to significant shortage of needed human resources in the National Health System) and shortages in intensive care unit (ICU) beds. These vulnerabilities have already been identified by the Federation of Hospital Doctors' Associations in a timely manner on the second day of the start of the coronavirus epidemic in Greece.28

The Ministry’s of Health initial management, as reflected in the Legislative Content Act of the 25th February (which is the previous day of the official start of the epidemic in the country),29 was the cancellation of health workers leaves, the internal movement of the health personnel within the National Health System, the hiring at EODY[the greek CDC] with 4-month contracts and the use (with appropriate compensation) of private-sector ICU beds (the so-called 'health start-up of PPPs in Greece’). It is a matter of great concern whether these measures could overcome the structural vulnerability of the health care system in view of the faced challenge.

The partial reframing of the Ministry's initial assessment, as reflected in the Legislative Content Act of 11 March (three weeks after the outbreak in the country),30 that, measures such as hiring of auxiliary staff at the NHS with two-year contracts and the exchange of medical equipment between the Health Regions and the NHS hospitals are sufficient to shield the health system, is also a matter of concern.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

The health of the populations is particularly important and vulnerable to be trusted, especially in the context of a global public health threat, to the choices of WHO philanthropists, the performance of speculative pandemic bonds internationally or in the expected benefits of PPPs in health at national level, whose ineffectiveness, at best, has already been evaluated in Europe 10 years ago.31

The continuation and extension of the measures implemented to control and delay the spread of the new coronavirus disease, is urgently needed to be accompanied by a parallel comprehensive reinforcement of the NHS, with an emphasis on the full support of existing health care staff, hiring of the needed permanent staff and providing the necessary fiscal space with a generous increase in state funding, for the appropriate functioning of the health system in conditions of increasing health care need and use.

References:

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation report 52. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) outbreak in China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;E1–4.

3. Editorial. COVID-19: too little, too late? Lancet. 2020;395:755.

4. ΕΟΔΥ. Ενημέρωση διαπιστευμένων συντακτών υγείας από τον εκπρόσωπο του Υπουργείου Υγείας Καθηγητή Σωτήρη Τσιόδρα - 12/03/2020. Αθήνα: Εθνικός Οργανισμός Δημόσιας Υγείας; 2020.

5. ΕΟΔΥ. Ενημέρωση διαπιστευμένων συντακτών υγείας από τον εκπρόσωπο του Υπουργείου Υγείας Καθηγητή Σωτήρη Τσιόδρα - 03/03/2020. Αθήνα: Εθνικός Οργανισμός Δημόσιας Υγείας; 2020.

6. World Health Organization. Novel coronovirus (2019-nCoV). Donor alert. Geneva: World Health Orgnanisation; 2020

7. World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation report 51. Geneva: World Health Orgnanisation; 2020.

8. Khabbaz R. Still learning from SARS. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:780–1.

9. World Health Organization. International Health Regulations (2005). Third edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

10. Evans DK, Goldstein M, Popova A. Health-care worker mortality and the legacy of the Ebola epidemic. Lancet Glob Heal. 2015;3:e439-440.

11. Flessa S, Marx M. Ebola fever epidemic 2014: a call for sustainable health and development policies. Eur J Heal Econ. 2016;17:1–4.

12. Jonas O. Pandemic bonds: designed to fail in Ebola. Nature. 2019;572:285.

13. Mullan Z. The cost of Ebola. Lancet Glob Heal. 2015;3:e423.

14. Checchi F, Waldman RJ, Roberts LF, Ager A, Asgary R, Benner MT, et al. World Health Organization and emergency health: if not now, when? BMJ. 2016;352:i469.

15. World Health Organization. Contributions to the WHO COVID-19 appeal for US$61.5 million. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

16. Stein F, Sridhar D. Health as a ‘global public good’: creating a market for pandemic risk. BMJ. 2017;358:j3397.

17. World Bank. World Bank Group announces up to $12 billion immediate support for covid-19 country response. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2020.

18. International Monetary Fund. IMF makes available $50 billion to help address coronavirus. Washington DC: International Monetary Fund; 2020.

19. World Health Organization. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): strategic preparedness and response plan. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

20. Brim B, Wenham C. Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility: struggling to deliver on its innovative promise. BMJ. 2019;367:I5719.

21. A pussyfooting cat bond. The Economist. 7th March 2020;65.

22. Kondilis E, Bodini C, De Vos P, Benos A, Stafanini A. Politiques fiscales en Europe a l’ere de la crise économique. Sante Conjug. 2014;34–43.

23. Jesus TS, Kondilis E, Filippon J, Russo G. Impact of economic recessions on healthcare workers and their crises’ responses: Study protocol for a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative evidence for the development of an evidence-based conceptual framework. BMJ Open. 2019;9:3–7.

24. Ferrè F, De Belvis AG, Valerio L, Longhi S, Lazzari A, Fattore G, et al. Italy health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2014;16.

25. Carinci F. Covid-19: preparedness, decentralisation, and the hunt for patient zero. BMJ. 2020;368:m799.

26. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. WHO rapid response team concludes mission to Italy for COVID-19 response. Copenhagen: WHO regional office for Europe; 2020.

27. Ministero della Salute. Covid-19 - Situazione in Italia. Rome: Ministero della Salute; 2020.

28. Federation of the Associations of Hospital Physicians in Greece- OENGE [Ομοσπονδία Ενώσεων Νοσοκομειακών Γιατρών Ελλάδας]. OENGE for covid 19: the difference between responsibility and covering the issue. Athens 2020 [in greek].

29. Act of Legislative Content. Urgent measures to avoid and limit the spread of coronavirus. ΦΕΚ Α΄. 2020; 42: 763–7. [in greek]

30. Act of Legislative Content. Urgent measures to address the negative consequences of the onset of coronavirus Covid-19 and the need to limit its spread. ΦΕΚ Α΄. 2020; 55: 997–1005.[in greek]

31. Kondilis E, Antonopoulou L, Benos A. Public-private sector partnerships in hospitals: ideological preference or empirically based choice in health policy? Archives of Greek Medicine. 2008; 25: 496–508. [in greek]